Visual

constructed images

Visual

constructed images

Visual

remembered images

Visual

remembered images

constructed

sounds

constructed

sounds

remembered

sounds

remembered

sounds

kinaesthetic (feelings and bodily sensations)

auditory digital (internal dialogue)

NLP TECHNIQUES

THE HISTORY OF NLP

(Neuro-Linguistic Programming)

NLP began in the early 1970's in Santa Cruz, California from the collaboration of John Grinder, an Assistant Professor of Linguistics and Richard Bandler, a psychology student at the time.

Bandler discovered he had a natural gift for modelling and hearing patterns. He discovered he could detect and replicate patterns in Gestalt Therapy (a form of psychotherapy) from minimum exposure. He became an editor for several of Fritz Perls' books in Gestalt therapy. Being familiar with Perls' work, Bandler began to study Perls' techniques. As he discovered that he could model Perls' therapeutic procedures, he began experimenting with clients using the techniques.

After enjoying immediate and powerful results from that modelling, Richard discovered that he could model others. With the encouragement of Grinder, Bandler got the opportunity to model the world's foremost family therapist, Virgina Satir. Richard quickly identified the "seven patterns" that Virginia used. As he and John began to apply those patterns, they discovered they could replicate her therapies and obtain similar results.

As a computer programmer, Richard knew that to program the simplest "mind" in the world (a computer with on and off switches) you break down the behaviour into component pieces and provide clear and unambiguous signals to the system. To this basic metaphor, John added his

extensive knowledge of transformational grammar. From transformational grammar we borrow the concepts of deep and surface structure statements that transform meaning/knowledge in the human brain. From this they began to put together their model of how humans get "programmed," so to speak.

Thereafter, world-renowned anthropologist Gregory Bateson introduced Bandler and Grinder to Milton Erickson, MD. Erickson developed the model of communication that we know as "Ericksonian Hypnosis." Since 1958, the American Medical Association has recognised hypnosis as a useful healing tool during surgery. As Bandler and Grinder modelled Erickson, they discovered they could obtain similar results. Today many of the NLP techniques result from modelling Ericksonian processes.

From these experiences and their research into the unifying factors and principles, Bandler and Grinder devised their first model. It essentially functioned as a model of communication that provided a theoretic understanding of how we get "programmed" by languages (sensory-based

and linguistic-based) so that we develop regular and systematic behaviours, responses, psychomatic effects etc.

Bandler and Grinder didn't intend to begin a new branch of psychology, they were not interested in developing theories. Their main goal was to identify patterns used by successful therapists and pass them on to others to use. From hours of observing these three excellent communicators, they went on to build their own model of therapy. The name was the last step, and after a marathon session of discussion (and several bottles of California wine) they came up with the name, "Neuro Linguistic Programming"

Neuro refers to our nervous system/mind and how it processes information and codes it as memory inside our very body/neurology. By neuro we refer to experience as inputted, processed, and ordered by our neurological mechanisms and processes.

Linguistic indicates that the neural processes of the mind come coded, ordered, and given meaning through language, communication systems, and various symbolic systems (grammar, mathematics, music, icons).

Programming refers to our ability to organise our sensory-based information (sights, sounds, sensations, smells, tastes, and symbols or words) within our mind-body organism which then enables us to achieve our desired outcomes. Taking control of one's own mind describes the heart of NLP.

NLP explores the relationship between how we think (neuro), how we communicate both verbally and non-verbally (linguistic) and our patterns of behaviour and emotion (programmes).

A few of the principles are listed below:

If you always do what you've always done, you will always get what you've always gotten.

The system (person/institution/country) with the most choices or flexibility has the best chance of success, survival, and/or influence.

While your intention may be clear to you, it is the other person's interpretation and response that reflects your effectiveness. NLP teaches you the skills and flexibility to ensure that the message you send equals the message they receive.

What seemed like failure is usually success that just stopped too soon. With this understanding, we can stop blaming ourselves and others, find solutions, and improve the quality of what we do.

Though a major project can seem overwhelming at first, defining and sequencing the steps can make it more easily achievable.

Words are only a small part of our total communication. Facial expressions gestures, posture, and voice quality are key components of nonverbal communication. Even when we remain silent, we are communicating. An effective communicator pays attention and responds to what happens both verbally and nonverbally in their interactions. When we learn to notice and respond at that level, the quality of our interactions increases dramatically.

By understanding that people have some positive intention for themselves in what they say and do, it's easier to stop getting angry and stuck, start to move forward, and enjoy more flexibility and grace.

All experiences are subjective - we respond to our internal representation of events, not to the events themselves.

· Each person is unique and uniquely valuable

· Everyone has all the resources they need for success - there are no unresourceful people, only unresourceful states

· Everyone makes the best choice available to them at the time

· Behind every behaviour is a positive intention

· There is no failure, only feedback

· A persons behaviour is not the person

· The meaning of a communication is the response you get

· Mind and body are part of the same system

· Experience has a structure - change the structure and you change the experience

· I am in charge of my mind and therefore my results

One of the principles of NLP is that we are always communicating, and most of our communication is other than words. The question becomes: "What are we communicating?" Is what we intend to convey the same as what the listener understands? If not, how do we recognize the cues and adjust? NLP de-mystifies the communication loops at home and work and gives us practical tools for becoming highly skilled communicators.

Language affects how we think and respond. The very process of converting experience into language requires that we condense, distort, and summarize how we perceive the world. NLP also provides questions and patterns to make communication more as we intend. NLP teaches us to understand how language affects us through implicit and embedded assumptions. Since advertisers, the media, and politicians use language to convey their messages, learning about language through NLP can also add awareness and consumer protection for your mind!

NLP processes are a result of discovering how experts or excellent leaders do what they do so well and teaching those skills to others. Modeling skills are at the heart of NLP. Learning the specific components of how others do something well will provide you with new options. One example the NLP spelling strategy, is modeled from naturally good spellers and is easily taught to children and adults. Other examples about in education, business, health, sports and personal life as well.

NLP describes, in very precise terms, the images, sounds, and feelings that make up our inner and outer world. How do we know what we know? How do we do what we do? For example, how do you know that a pleasant memory is pleasant? How do you know when to feel scared or happy at certain times? How do you like or dislike something? How do you learn a subject easily, or not? Sometimes people describe NLP as "software for our brains"

NLP is about how we "code" our experiences. When we understand the specific ways that our brains make distinctions, then it is easier to make changes, to learn, and to communicate effectively.

NLP is a tool to understand how an individual makes sense of the world. NLP studies individuals' experiences: how they perceive the world around them and how their brain makes specific distinctions for them. It does NOT assume that we all do this the same way. In NLP we know that each person has a unique style of learning, perceiving and responding to the world. NLP is inherently respectful of differences.

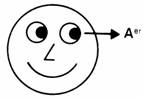

NLP EYE MOVEMENTS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

kinaesthetic (feelings and bodily sensations) |

auditory digital (internal dialogue) |

This is as you look at another person

EYE ACCESSING CUES

It is easy to know if a person is thinking at the moment in pictures, sounds or feelings. There are visible changes in our bodies when we think in different ways. The way in which we think affects our bodies and the way in which we use our bodies affects the way we think. We move our eyes systematically depending on how we are thinking. Neurological studies have shown that eye movement is associated with activating different parts of the brain. Although it is possible to move our eyes consciously in any direction while we are thinking, it is easier to access a particular representation system if we use the appropriate eye movements. Accessing cues also allow us to know how (but not what) a person is thinking and an important part of NLP training is to become aware of other people's eye accessing cues. It is, however, important to remember that these generalisations must be checked against experience. NLP is not a technique for categorising people into types. People always present more possibilities than our generalisations about them. NLP presents enough models to fit what people really do rather than trying to make the people fit the stereotypes.

LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATIONAL SYSTEMS

NLP consists of a number of models, and then techniques based on those models.

Sensory acuity and physiology.

Thinking is tied closely to physiology. People's thought processes change their physiological state. Sufficiently sensitive sensory acuity will help a communicator fine-tune their communication to a person in ways over and above mere linguistics.

Communication begins with our thoughts, and we use words, tonality and body language to convey these thoughts to other people. When we think about what we see, hear and feel, we recreate these sights, sounds and feelings inwardly. We re-experience information in the sensory form in which we first perceived it. Now, how do we remember something? One way in which we think is consciously or unconsciously remembering the sights, sounds, feelings, tastes and smells we have experienced. We use our senses outwardly to perceive the world and inwardly "re-present" the experience to ourselves. In NLP the ways we take in, store and code information in our minds -seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting and smelling -- are known as representational systems. The visual, auditory and kinaesthetic systems are the ones primarily used in Western cultures. The sense of taste and smell are not as important and are often included in the kinaesthetic system. We use all three of the primary systems all the time although we pay attention to one sense more than another depending on what we are doing.

When a person tends to use one internal sense habitually, this is called their preferred or primary system in NLP. We use language to describe our thoughts so our choice of words often indicates which representational system we are using. This is certainly important in establishing and keeping rapport. The secret of good communication is not so much what we say, but how we say it. One way to gain rapport, therefore, is to match predicates with the person you are speaking with in order to speak "their" language and facilitate communication.

Body language communicates something, regardless of whether we wish to communicate or not. Living systems cannot not communicate.

So what can body language teach us about other people? With sufficient exposure to another culture we can learn to recognise its members by their body language, the way they move and gesture, how close they stand to other people and how much eye contact they make and with whom. We can learn to recognise how any individual, whatever their origin, is thinking by watching their eye movements, breathing and posture as they interact. This will not tell us what they are thinking. The subject matter of someone's thoughts remains private until they describe it.

If we observe some interesting body language and ask the person what it means to them, we gain reliable information. If we observe the same person doing the same thing in a similar context in future, we can ask them if it means what they told us last time. This combination of observing a particular person and asking them for meaning for our future reference, is called calibration. We calibrate an individual against themselves in a particular context. In this way we can learn our employers' requirements, our partners' preferences and our pets' idiosyncrasies with some degree of accuracy.

We can use other people's body language to help us create rapport with individuals, groups and at parties. Instead of mind reading, if we place our attention on the other person or people, open our peripheral vision and quieten our internal comments we will notice the rhythm of their whole body movements, speech and gestures. If we match these rhythms with our own bodies we will find ourselves being included in what is going on. This is not the same as literal mimicry. Accurate imitation often gets noticed and objected to. The intent is to match the rhythm by making some form of movement in the same rhythm without attracting conscious attention to it. When we feel included we can test the level of rapport by doing something discreetly different and noticing whether the other or others change what they are doing in response. If they do, you can lead them into a different rhythm or influence the discussion more easily.

Strictly speaking, nonverbal vocal patterns are not body language, but they can be used to establish or break rapport as readily as physical movement. If we match the rate or speed of speech, the resonance, tonality and rhythm used by a person, we will create rapport with them. Again, out and out mimicry is not recommended. Most people will catch it happening. It is more comfortable to match voice patterns at the equivalent pitch in our own range than to attempt note for note matching and to match unfamiliar breathing rhythms with some other emphasis.

.

Representational systems.

These actually appeared in Erickson's work and the work of others, though Bandler and Grinder took them much further. Different people seem to represent knowledge in different sensory modalities. Their language reveals their representation. Often, communication difficulties are little more than two people speaking in incompatible representation systems.

For example, the "same"

sentence might be expressed differently by different people:

Auditory: "I really hear what you're saying."

Visual: "I see what you mean."

Kinesthetic: "I've got a handle on that."

What Type of Learner are you?

Think about yourself and also your friends, family members and teachers. Notice the way these people might prefer to learn and communicate.

We all have preferences for how we like information to be presented:

Some like to see what you mean .....

Some like to hear your idea .....

Some like to experience or feel what you are talking about ....

Similarly, we also have preferences for the way we evaluate and analyse information:

Some decide by how things look to them ......

Some decide by how things sound to them ......

Some decide by how things feel to them ......

Do you often catch yourself saying things like "That looks right to me," or "I get the picture"? Or are you more likely to say "That sounds right to me," or "That rings a bell"? Expressions like these may be clues to your preferred modality.

PREDICATE WORDS AND PHRASES

|

VISUAL (see)

to appear clarity clear cloudy to demonstrate to examine to focus focus glance illusion to illustrate image to look to notice observe obvious outlook picture preview to reflect to see scene to show sight view vision to watch

it appears to me to catch a glimpse of it's clear-cut to see eye to eye on s.th. it's a hazy idea in light of in view of it looks like to make a scene photographic memory to put it in black & white to see to it it seems to me to be short-sighted to show off sitting pretty to take a look to be up front |

AUDITORY (hear)

to announce to articulate to ask to communicate to converse to discuss gossip to hear to listen loud to mention noise oral remark to ring rumour to say silence sound to speak speechless to talk to tell tone to verbalise vocal voice

blabber-mouth clear as a bell clearly expressed to describe in detail for a song to get an earful to express yourself give me your ear to hear voices to hold your tongue loud and clear money talks pay attention to to be out-spoken to play it by ear it rings a bell tattle-tail to tell the truth it's unheard of word for word |

KINESTHETIC (feel)

active bearable to clash concrete emotional to feel firm foundation to grasp heated to join intuition lukewarm nervous pressure rush shock sensitive soft solid stress structured to support tension tangible to touch unbearable

control yourself to get a handle on s.th. to get in someone's hair to get in touch with to get the drift of s.th. to get off somone's back hand-in-hand heated argument hold on to be a hot-head keep your shirt on to lay the cards on the table to not follow s.o. to pull some strings it slipped my mind to stir up trouble to start from scratch to be a stuffed shirt topsy-turvy to be underhanded |

|

Teaching Styles: Instructional Presentation taken from „Righting the Educational Conveyer Belt“ by Michael Grinder

|

||

|

Visual |

Kinesthetic |

Auditory |

|

Talks fast |

Talks more slowly |

Speaks rhythmically |

|

|

|

|

|

Uses visual aids (overhead, board) |

Uses manipulatives (hands‑on and handouts) |

Likes class discussion |

|

|

|

|

|

Likes to cover a lot of content |

Has student involved projects (plays, simulations) |

Teacher or student reads text aloud |

|

|

|

|

|

Considers forms important (grammar. spelling, heading) |

Considers concepts important (tends to de‑emphasize spelling and grammar) |

Tends to acknowledge student's comments by paraphrasing |

|

|

|

|

|

Believes in visual feedback to evaluate individual ‑(tests) |

Believes in what students can do (create, demonstrate, etc.) to evaluate |

Disciplines by talking to the student usually with memorized sermonettes which begin with "How many times? . . ." |

|

|

|

|

|

Is due date oriented |

Has students do boardwork, working in units and teams |

Is easily disoriented from focus of lesson (war stories) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Uses lots of demonstrations |

Rarely uses visual aids, has a running commentary of words and noises (i.e., "Okay," "Uh huh") |

Behaviour Indicators

|

Visual |

Auditive |

Kinaesthetic |

|

Organised |

Talks to self |

Responds to physical rewards |

|

Neat and orderly |

Easily distracted |

Touches people and stands close |

|

Observant |

Moves lips/says words when reading |

Physically oriened |

|

Quieter |

Can repeat back |

Moves a lot |

|

Appearance orientated |

Math and writing more difficult |

Larger physical reaction |

|

More deliberate |

Spoken language easy |

Early large muscle development |

|

Good speller |

Speaks in rhythmic patterns |

Learns by doing |

|

Memorises by picture |

Likes music |

Memorises by walking, seeing |

|

Less distracted by noise |

Can mimic tone, pitch and timbre |

Points when reading

|

|

Has trouble remembering verbal instructions |

Learns by listening

|

Gestures a lot

|

|

Would rather read than be read to |

Memorises by steps, procedure, sequence |

Responds physically

|

|

Voice |

|

|

|

Chin up, voice high |

„Marks off“ w/ tone, tempo, shifts |

Chin down, voice louder

|

|

Learning |

|

|

|

Needs overall view and purpose and a vision for details; cautious until mentally clear |

Dialogues both internally and externally; tries alternatives verbally first |

Learns through manipulating and actually doing

|

|

Recall |

|

|

|

Remembers what was seen |

Remembers what was discussed |

Remembers an overall impression of what was experienced |

|

Conversation |

|

|

|

Has to have the whole picture; very detailed |

Most talkative of three models; loves discussions, may monopolise; has a tendency for tangents and telling whole sequential event |

Laconic; tactile, uses gestures and movements uses action words |

|

Spelling |

|

|

|

Most accurate of three models; actually sees words and can spell them. Confused when spelling words never seen before |

Uses phonetic approach, spells with a rhythmic movement |

counts out letters with body movements and checks with internal feelings |

|

Reading |

|

|

|

Strong, successful area has speed |

Attacks unknown words well, enjoys reading aloud and then listening; often slow because of subvocalising |

Likes plot oriented books, reflects action of story with body movement |

|

Writing |

|

|

|

Having it look OK important, learning neatness easy |

Tends to talk better than writes and likes to talk as he writes |

Thick pressured handwriting not as good as others |

|

Imagination |

|

|

|

Vivid imagery, can see possibilities, details appear; is best mode for long term planning |

Sounds and voices heard |

Tends to act the image out; wants to walk through it Strong intuitive weak on details |

If you couldn't see or hear, or if you couldn't feel texture, shape, temperature, weight, or resistance in the environments, you would literally have no way of learning. Most of us learn in many ways, yet we usually favour one modality over the others. Many people don't realise they are favouring one way, because nothing external tells them they're any different from anyone else. Knowing that there are differences goes a long way toward explaining things like why we have problems understanding and communicating with some people and not with others, and why we handle some situations more easily than others.

How do you discover your own preferred modality? One simple way is to listen for clues in your speech, as in the expressions above. Another way is to notice your behaviour when you attend a seminar or workshop. Do you seem to get more from reading the handout or from listening to the presenter? Auditory people prefer listening to the material and sometimes get lost if they try to take notes on the subject during the presentation. Visual people prefer to read the handouts and look at the illustrations the presenter puts on the board. They also take excellent notes. Kinaesthetic learners do best with "hands on" activities and group interaction.

The following characteristics will help you zero in on your best learning modality.

It's easy to decipher the modalities of other people in your life by noticing what words they use when they are communicating. These words are called predicates, or "process words." When a situation is perceived in someone's mind, it's processed in whatever modality the person prefers; the words and phrases the person uses to describe it reflect that person's personal modality.

Once you identify a person's predicates, you can make it a point to match their language when you speak to them. Besides using process words that the person can relate to, you can also match the speed at which they talk. Visual speak quickly, auditories at a medium speed, and kinaesthetics more slowly.

Matching your modality to another's is a great way to create rapport and an atmosphere of understanding.

Task 1: Here you can find a dialogue between an English teacher and a student. The teacher wants to explain the difference between adverb and adjective, the student on the other hand just can’t understand it. What went wrong? Can you give the teacher any advice? What would you have done in such a situation?

"Dialog" : Lehrer - Schüler

Lehrer :

Also ich sehe jetzt, dass du das Problem Adverb - Adjektive überhaupt nicht unter dem richtigen Blickwinkel betrachtest. Sieh mal, die farbigen Pfeile zeigen doch ganz deutlich, dass du zuerst wissen musst, worauf es sich bezieht.

Schüler:

Sicher, ich habe das Gefühl, dass Sie recht haben, aber ich kann überhaupt nicht begreifen, warum ich es nicht pack herauszufinden, ob es ein Adverb oder ein Adjektive ist. aufzustellen.

Lehrer:

So ganz sehe ich dein Problem noch nicht, betrachten wir dieses Problem in einem anderen Licht, schau mal genau hin, es ist doch deutlich zu erkennen, dass ein Adverb sich immer auf ein Verb oder ein anderes Adjektiv bezieht.

Schüler:

Also wissen Sie, ich ..äh..na ja, ich habe da so ein Gefühl, bis zur Englischschularbeit kriege ich die Sache nicht mehr in den Griff.

Lehrer:

Na ja, du wirst schon sehen, am Ende des Tunnels gibt es auch wieder Helligkeit, mir ist jetzt nur wichtig, dass wir uns gemeinsam anschauen, wie es am Ende des Weges aussieht, den wir noch bis Ende des Schuljahres vor uns haben.

Schüler:

Ich begreife im Moment noch nicht, was ich tun soll, ich habe irgendwie das Gefühl, dass ich mich nicht mehr mit Grammatik auseinandersetzen kann, das bringt doch sowieso nichts. Manchmal habe ich richtig Lust, so richtig auf den Tisch zu klopfen .

Lehrer:

Wichtig ist doch einfach, dass du zunächst mal den richtigen Einblick bekommst. Es sieht bei dir im Moment - was Grammatik angeht - mehr so wie auf einem Trümmerfeld aus. Sicher hast du jetzt - nach deiner eigenen Betrachtung der Fakten, die du mir ja farbig genug ausgemalt hast -eine andere Sichtweise bekommen.

Schüler:

Wissen Sie, ich versuche schon die ganze Zeit, Ihnen zu sagen, dass die Grammatik eine Sache für mich ist, die voller Haken und Ösen ist, in die ich mich ständig verfange. Ich habe den Eindruck, Sie verstehen einfach nicht, worum es bei mir geht. Ich versuche halt, die Sache so gut es geht in den Griff zu kriegen. Aber ich pack's einfach nicht. Ich weiß einfach nicht, worum es sich da dreht.