PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

1) Provide meaningful tasks

Recent trends in methodology have stressed the need for meaningful activities in the classroom. There are a variety of reasons for this, among them the swing towards realism and authenticity and the need to engage

learners in activities which will enable them to be more self-reliant. Equally important here is the fact that more meaningful tasks require learners to analyse and process language more deeply, which helps them to commit information to long term memory. The theory that a

student's 'personal investment' has a very positive effect on memorisation is one that many teachers and learners will intuitively agree with.

An experiment by Wilson and Bransford provides an interesting insight here. In this experiment, three different groups of subjects were used.

The first group were given a list of thirty words and told that they would be tested on their ability to recall the words.

The second group were given the same list of words and told to rate each word according to its pleasantness or unpleasantness; they were not told that they would be tested on their ability to recall the

words.

The third group were given the list and asked to decide whether the items on the list would be important or unimportant if they were stranded on a desert island. They too were not told that they would be

tested on these items.

The results of the tests showed a similar degree of recall between groups one and two, while group three recorded the highest degree of recall. This experiment illustrates several important points:

1 That the intention to learn, however laudable, does not in itself ensure that effective learning will take place.

2 That subjects are more likely to retain verbal input (i.e. commit new items to long term memory) if they are actively engaged in a meaningful task that involves some kind of semantic processing, and

provides a unifying theme to facilitate organisation in the memory.

Guided discovery

is another way in which teachers can engage the students' interest and involve them in a level of semantic processing which should promote more effective learning and retention. An important qualifying statement here is that the students have the means to

perform the learning task, otherwise they will become frustrated and lose motivation.

Consider the following methods of presenting the item 'to swerve'.

- The teacher explains that 'swerve1 is a verb and means to change direction suddenly. He exemplifies this on the board with the sentence 'the car swerved to avoid the child', and then conducts some drilling of

the example sentence.

- The teacher asks the question, 'Why would you swerve in a car?' The students are then supplied with dictionaries to look up the word 'swerve' and told to write their answer on a piece of paper.

The first presentation is probably quite adequate to convey the meaning of 'swerve', but the second approach may be more memorable for the learners. Not only does it involve an element of guided discovery, but it also engages the students in a

degree of

semantic analysis i.e. what causes somebody to swerve; this is not required of them in the first presentation.

2. Create images

Teachers often make extensive use of visual images in the classroom for illustrating meaning. One further advantage of this is that our memory for visual images is extremely reliable and there is little doubt that objects and

pictures can facilitate memory. Equally obvious is that it is easier to conjure up a mental image of a concrete item than an abstract one; try, for instance, to 'image' the following: 'bottle', 'dog', 'truth', 'life'. You will probably have had no difficulty with the first two,

but it is extremely difficult to supply a visual image for 'truth' and 'life'.

|

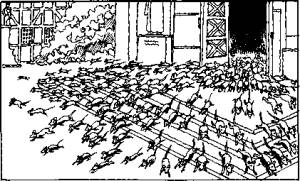

Our ability to produce mental images has led to a memory technique known as the key word technique. It consists of associating the target word with a word which is pronounced or spelt similarly in the mother tongue,

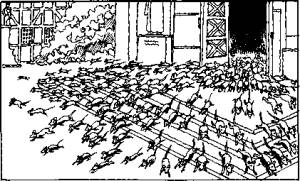

but is not necessarily related in terms of meaning, e.g. Rathaus ( meaning 'town hall') sounds like 'rat house' in

English.

The learner then conjures up a visual image of a lot of rats coming out of his local town hall, for instance.

|

|

It appears to aid memory if the meaning and the key word are made to interact, as in the case above.

Some claims are also made that the more bizarre the

image, the easier it will be to recall, but the evidence for this is unconvincing.

|

|

Task: Try o find other images of the key word technique

|

Facilitate imaging and concreteness

According to the dual coding theory of human memory (Clark and

Paivio), the mind contains a network of verbal and imaginable representations for words:

Learning foreign vocabulary . . . involves successive verbal and nonverbal representations that are activated during initial study of the word pairs and during later efforts to retrieve the translations. (1991: 157)

When learners image to-be-learned material, the possibility for later recall is much greater than if they only make verbal links.

Organize the material

To build verbal representations in the memory instructors need to present vocabulary in an organized manner. Since it is harder to memorize random material, arrange vocabulary in units, introduce it in stages, and

summarize.

To build non-verbal representations, elaborate: make illustrations, show pictures, draw diagrams, and list details.

Capitalizing on verbal and non-verbal links appears to be worthwhile; however, a word of caution is necessary regarding which words are initially presented together. If the linked words or representations include

both similar and different features, such as in the case of antonyms, cross-association may take place. This may result in the words actually being more difficult to learn.

Another aspect of the dual coding theory is that learning is aided when material is made concrete (psychologically 'real') within the conceptual range of the learners.

This may mean:

- giving personal examples,

- relating words to current events,

- providing experiences with the words,

- comparing them to real life or better yet,

- having students create these images and relate the words to their own lives.

This tapping into past experience is an important part of the dual coding theory. In a study of ESL students' word associations, Sökmen (1993) found that the majority of associations were those which reflected strong memories, attitudes, or

feelings, that is, that words appeared to be stored with images of past experiences. Vocabulary instruction which relates new vocabulary to past experience has the potential of enhancing memory.

3. Plan rote learning

Another memorisation technique which has a long history in language learning is rote learning. This involves repetition of target language items either silently or aloud and may involve writing down the items (perhaps

more than once). These items commonly appear in list form;

- Typical examples being items and their translation equivalent (e.g. door = die Tür),

- items and their definitions (e.g. nap = short sleep),

- paired items (e.g. hot-cold, tall-short),

- and irregular verbs.

A common practice is for the learner to use one side of the list as prompts and cover the other side in order to test himself.

In the early stages of language learning, repetition gives the students the opportunity to manipulate the oral and written forms of language items, and many learners derive a strong sense of progress and achievement from this type of activity. For this

reason it can be very valuable. It may also be a very legitimate means of transferring items into long term memory where there is a direct mother-tongue equivalent and very little semantic coding is involved in the learning process. For universal paradigms such as days of the

week, or for irregular verbs (as long as the meaning of the verb is known), a mechanical learning activity of this type may be quite useful.

However, earlier I indicated that a far deeper level of processing is required to commit items to long term memory and I illustrated the type of processing that will be involved. In addition, lists of translation equivalents may be counter-productive for

learners, as memorisation of this type may delay the process of establishing new semantic networks in a foreign language.

Task:

Write down some examples for this type of learning vocabulary

4. Ensure recycling

The importance of recycling previously presented lexis is a direct consequence of the theories of forgetting. If memory traces do gradually fade in the memory without regular practice then it is clearly necessary that we

create opportunities in the classroom for students to practise what they have learnt. And given that other learning activities will interfere with effective retention of new lexis, we should try to ensure that practice is carefully spaced and that students are not being

overloaded with too much new lexis at any one time. This will be a function of the course designer as much as the teacher, but only the teacher can accurately measure the extent of recycling or the pacing of new input that will be appropriate for their students on a daily or

weekly basis. With regard to the theory of cue-dependent forgetting, it will also be a function of recycling that students are being

asked to locate items in their long term memory. Developing effective retrieval systems may not require lengthy practice and can easily be incorporated into the lesson by way of 'warmer' activities at the beginning. The teacher could, for example, give

the students an appropriate retrieval cue for vocabulary presented in the previous lesson and see how many items the students can recall. Alternatively he could present the students with disparate items presented over several lessons and ask the students to organise them into

different categories. Both activities are helping to assist the process of subjective organisation so essential to effective retention and recall.

As mentioned earlier the rate of forgetting also has implications for the recycling of lexical input. If eighty per cent of what we forget is lost within twenty-four hours, there is a strong argument for revising new language items one day

after initial input. In The Brain Book (1979), Peter Russell actually sets out a revision schedule to ensure that new material is permanently recorded. His timetable is as follows:

1 A five-minute review five to ten minutes after the end of a study period.

2 A quick review twenty-four hours later.

3 A further review one week later.

4 Final reviews one month later and then six months later.

Task

: Is such a detailed plan of campaign realistic?

It should still be possible for teachers to incorporate some of this organised recycling into their lessons.

Suggestions:

- A regular use of warmer activities at the beginning of a lesson to aid recall and develop retrieval systems;

- Teachers try to include a quick review of important lexis one to two days after initial input. This should help to compensate for any decline in the memory trace, and combat the effects of interference which crowd the memory with new

information, making it difficult to locate previously learned lexis.

- With regard to further recycling, weekly or monthly progress tests (the choice depending on course duration and intensiveness) are probably the easiest and most practical way of ensuring some check on previously learned lexis.

One final point about recycling is that it is not just a matter of quantity but also of quality. Although teachers provide example sentences for new lexical items they are not in the habit of illustrating the item

with three or four different examples. They might argue that it would be too time-consuming to present so many examples, and in any case why give four examples when one will do? The problem of time is inescapable and there is a danger that varied examples can be overwhelming for

the students and lead to more confusion than understanding. In the long term, though, students will find it easier to retain and retrieve an item

from long term memory if they have been exposed to it through a number of different

contexts. And this will be just as true for your own understanding of vocabulary teaching. Imagine reading a book four times. You may learn something on the second reading that you missed on the first, but you are unlikely to gain very much on the third or fourth readings.

Compare that with reading four different books on the same subject where you have the opportunity to meet similar subject matter but each time seen from a slightly different point of view. Initially this may be confusing but eventually you will gain far more insight and depth of

understanding, and this in turn will fix the ideas more permanently in your long term memory. Following the restricted contextualisation of new lexis for initial teaching purposes, it will therefore become a function of recycling to expand the context range of an item and so

facilitate retention and recall.

Task: Summarize the most important information on “Recycling”.

Task: Try to find a metaphor/imagery for the recycling model

|

|

|

5 minutes 24 hours 1-2 weeks 1 month six months

|

5. Provide a number of encounters with a word

As the student meets the word through a variety of activities and in different contexts a more accurate understanding of its meaning and use will develop. Various studies create a range of 5-16 encounters with a word in order

for a student to truly acquire it.

Therefore, an important aspect of this gradual learning is that the instructor consciously cue reactivation of the vocabulary.

Reencountering the new word has another significant reward. According to theories of human memory (Baddeley):

... the act of successfully recalling an item increases the chance that that item will be remembered. This is not simply because it acts as another learning trial, since recalling the item leads to better

retention than presenting it again; it appears that the retrieval route to that item is in some way strengthened by being successfully used.

When a word is recalled, the learner subconsciously evaluates it and decides how it is different from others s/he could have chosen. He continues to change his interpretation until he reaches the range of meanings that a native speaker has (Beheydt,

1987). Every time this assessment process takes place, retention is enhanced.

In addition, if the encounters with a word are arranged in increasingly longer intervals, e.g. at the end of the class session, then 24 hours later, and then a week later, there is a greater likelihood of long-term storage

than if the word had been presented at regular intervals. According to this concept of graduated interval recall, the length of the word, its frequency, and whether it is a cognate for the learner will affect the number of recalls necessary; However, instructors can generally

rely on the 'ideal' schedule (Pimsleur, 1967). Therefore, the teacher needs to provide initial encoding of new words and then subsequent retrieval experiences. A number of common games can be employed in classrooms to recycle vocabulary, e.g. Scrabble, Bingo, Concentration,

Password, Jeopardy. As they provide yet another encounter with the target words, they have the advantage of being fun, competitive, and consequently, memorable.

6. Present a Picture dictionary

In the first two volumes of “THE NEW YOU &ME a great part of the new words are introduced with the help of “Picture Dictionaries”. You can find them most likely at the beginning of a new Unit. In

some units there are even two “Picture Dictionaries”

Introducing and establishing words:

Remember to introduce the words the multi-sensory way. The more all senses (visual, auditive, kinesthetic) are involved when introducing the meaning, the pronunciation and the spelling of a word, the more successful the word/structure will be stored and recalled again. Apart from that fact a

multi-sensory presentation of new words will also guarantee that you meet the needs of the various learning types in a class.

The Procedure

The following steps show a proven procedure of such a multi-sensory approach with the help of a Picture Dictionary.

|

Legend:

V = visual, a = auditive, k = kinesthetic; vi = visual internal ( when picturing an image with the eyes

closed), ki = kinesthetic internal (when imaging a movement – also articulation – as if you actually acted it out)

| Ask your students to open their books and look at the Picture Dictionary. Read word by word aloud. Explain the meaning through mime and gesture

– if necessary. Only in exceptional cases it will be necessary to translate the word.

|

|

| Ask the students to close their eyes and read the words slowly and distinctly again. Ask the students not to repeat the words.

|

a

|

| Ask the students to keep their eyes closed. Read the words again and ask them to echo the

words the same way as they have heard them. Vary your voice: One word aloud, the next word you may whisper, the next one at high pitch, the next one slowly, then quickly etc. Ask them to picture the word in the Picture Dictionary in their minds.

|

a

vi

|

| Read my lips: Ask the students to open their eyes again. Mouth the words without using your voice. The students are asked to guess which word you “said”.

|

v

ki, a

|

| What’s the missing word? Pair work: A closes his/her eyes, B covers (with an eraser etc.) the word (not the picture) in the Picture Dictionary. B asks, “What’s the missing word?” A names it and ask B now to close his/her eyes. With high ability groups they

can even cover two and more words.

|

k

vi

, a

|

| Visual anchoring. Ask your students to take a pencil. Name one word after the other from the Picture Dictionary and link it with a number. (e.g. one…angry, two…late, three…) and ask the students to write the numbers next to the pictures of the Picture

Dictionary. The students are asked to memorize the words with the appropriate numbers. Give them some time to do that. Now ask them to close their books. Name a number. The students name the matching word.

|

a

v

k

|

|

|

|

Additions

Ad 1.

Variants

· Instead of the Picture Dictionary in the book drawings / words can be reflected on the board by an overhead-projector.

· Another variant are sketches made by you on the board.

·

You can also use flashcards made of thicker paper ( 25x20 cm for the drawings, 25X25 for the words)

Advantage: Students can focus their attention better on one

presentation board and don’t get distracted by stories and other pictures and exercises in the book.

Procedure:

·

Show the pictures first and fix them with adhesive-tape or Blu Tack on the board. Try to evoke associations from the children.

·

When all the pictures are on the board, show the word-pictures and name them simultaneously.

·

It’s also motivating for the students if they can “see” the word-picture” only a second and then they guess what word it might be. It is fascinating to see how many students are able to get a global picture of a word in such a short

period of time.

·

Ask the students to match the word-pictures and the pictures.

·

Additionally to introducing each new word by showing a picture and the word-picture you can link the word with a typical gesture, mime or facial expression. Ask the students to imitate you.

Probable procedures:

·

Repeat the words several times.

·

After a few revisions just say the words and ask the students to mime it.

·

Later on you only mime they word and they have to name it.

Ad 4.

This exercise can be done in partner work. It’s more intensive and gives each student the chance to participate more often.

·

Establish the new words with the help of the four skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing).

·

Make sure the students also use the words and structures in a different context (Transfer)

·

The more the students are personally and emotionally involved in the process of acquiring a language, the more efficient it will turn out to be.

·

Speak as much English as possible in the classroom.

·

You can guarantee an efficient learning not by talking about the language, but by acquiring it as means of communication.

7. Infer word meaning from context

Providing incidental encounters with words is a method to facilitate vocabulary acquisition.

The students are asked to recognize clues in the context, or to use monolingual dictionaries.

Contextual guessing may be especially helpful to students with high proficiency.

Yet, the arguments for not focussing solely on implicit instruction to facilitate second language vocabulary acquisition come from a number of problems associated with inferring

words from context.

- Acquiring vocabulary mainly through guessing words in context is

likely to be a very slow process.

- Inferring word meaning is an error-prone process. Students

seldom guess the correct meanings Especially students with low level proficiency in the target language are often frustrated with this approach.

- Even when students are trained to use flexible reading

strategies to guess words in context, their comprehension may still be low due to insufficient vocabulary knowledge

- Guessing from context does not necessarily result in long-term

retention. What it takes to guess the meaning of an unfamiliar word is not necessarily what it takes to store it in one’s memory.

8. Integrate the new words with the old

According to lexico-semantic theory, humans acquire words first and then, as the number of words increases, the mind is forced to set up systems which keep the words well-organized for retrieval. The human lexicon is,

therefore, believed to be a network of associations, a web-like structure of interconnected links. If L2 students are to store vocabulary effectively, instructors need to help them establish those links and build up those associations.

When students are asked to draw on their background knowledge, their schema, they connect the new word with already known words, the link is created, and learning takes place. In the process of deciding how the new word fits in, i.e. how it is similar to or different from words

they already know, information about the word becomes more organized and we know from memory theory, that organized information is easier to learn.

There are a variety of class activities which draw on background knowledge, stimulating students to explore the relationships between tie to-learn word and words already known. Two examples are semantic mapping and charting semantic features. In each case students are asked to integrate the new with the old, while discriminating word meaning.

Better learning will take place when a deeper level of semantic processing is required because the words are encoded with elaboration (Craik and Lockhart, 1972.). When students are asked to manipulate words, relate them to

other words and to their own experiences, and then to justify their choices, these word associations are reinforced. Students need to be encouraged to think aloud, give reasons for their word choices, and to extend their learning of the world outside of the classroom, e.g. report

when they encounter the target ' word in the real world (Beck, McKeown, and Omanson, 1987).

Describing a target word to the student until the meaning is clear, is one way to engage the learner in deeper processing.

Techniques:

a) “What is it? technique”:

An example for learning the word ' stirrup:

A stirrup is silver. A stirrup is strong. A stirrup is made of iron. A stirrup has a flat bottom. We can find a stirrup on a horse. A stirrup is used to put your foot into when you ride a horse.

Since the meaning is not quickly given away, the learner has a reason to continue to process all of the input, until it is understood.

b) “Order the words”

Another example of encouraging deeper encoding is asking students to describe how a word, in this case order, is distinguished from similar ones. The directions are to cross out the word in each series which does not belong.

(a) order: command advise demand

(b) order: tell instruct suggest

In the process of deleting one, the characteristics which categorize the others will emerge. An even richer opportunity comes from having students supply the initial synonyms for this activity.

c) Giving more meanings e.g. polysemous words

Visser's (1990) underlying meaning technique is an example of a classroom activity which tries to promote a more in-depth understanding of a word. In her example, students are given a polysempus word in two contexts:

(a) If people or things saturate a place or object, they fill it so completely that no more can be added.

(b) If someone or something is saturated, they are extremely wet.

Then they are encouraged to interact in small groups, discussing questions which focus their attention on the similar feature or idea within this word. For example, what happens when cheap imported goods saturate the market? Can you get saturated with

sweat? From their discussion, students have to decide what the similar features/ideas are in (a) and (b) and determine an underlying meaning of saturate. Whatever classroom

techniques are applied, the degree of processing required will have an important effect on how well the words are remembered.

10. Use a variety of techniques

Those students who are most successful use several vocabulary learning strategies and this mixed approach continues to be advocated (McKeown and Beck, 1988; Stoller and Grabe, op. cit.). A mixed approach is

particularly appealing to students because it breaks up the class routine while building a variety of associational links. It also has a greater chance of harmonizing with the various verbal and non-verbal learning styles which different students may have.

Six categories of instructional ideas:

'dictionary work', word unit analysis, mnemonic devices, semantic elaboration, collocations and lexical phrases, and oral production.

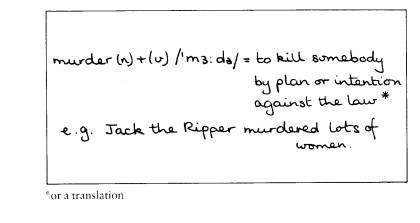

10. 1 Dictionary work

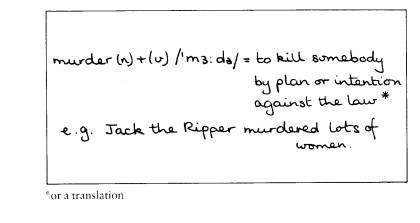

Most collecting and maintaining of vocabulary can be termed as 'dictionary-work', i.e. routines which focus on the word and its definition. The definition may be in L1 or L2. 'Dictionary work', especially the copying of words, provides an

opportunity to set up memory links from visual as well as motor traces.

Some examples of 'dictionary work' are:

a) highlighting the word where found and glossing its meaning in the margin

b) copying the word a number of times while saying it or while visualizing its meaning

c) translating

Traditionally, most learners were encouraged to list vocabulary items as they were learnt in a chronological order. The most common way of indicating meaning was to assign a mother-tongue equivalent to each item - our French vocabulary

notebooks looked something like this:

l´arbre (m) = Baum

léger (adj.) = Licht

écouter (v) = zuhören

Although this system gives us a very basic form of information about the most common meaning of an item as well as its part of speech and gender, the

organisation represents a very one-dimensional view of language. It does not reflect the types of associations we have just discussed, and

an arrangement like this is likely to present hurdles to the learner rather than facilitating the learning process. Lack of contextualisation will encourage the learner to assume that “léger” could be used in the context of 'a light room' (i.e. the opposite of dark)

and this would be quite wrong. Moreover, this system of storage is not flexible; it does not allow for later additions or refinements as one's knowledge of the uses and derivatives of an item increases, and gives us no indication here of the pronunciation of the items.

d) copying the word and then looking up the definition

|

A more comprehensive framework is given below and it is important to encourage students to store items with the relevant information. They should also leave space so that

they can add to the entry where need be:

|

e)

copying the word, looking up the definition, and then paraphrasing it ,

f)

creating a set of index cards of the words or morphemes and their definitions or words with pictures

g) matching words with definitions, in conventional exercises or on computer vocabulary programs

h) Labelling

Giving students pictures with objects to label is clearly an effective form of storage; most course books contain useful visuals of this type and labeling can be a class or homework activity. Many students (not only children) enjoy drawing and

it is worth exploiting this where possible as a storage device. It has the advantage both of the 'personal investment' of having drawn and labelled an item as well as being a simple and effective indication of meaning. (Whether the drawings are good or not is irrelevant; what

matters is that they should be recognisable to the learner.)

'Dictionary work', including practising good dictionary skills, is useful as an independent vocabulary acquisition strategy. Since students may come to the language classroom without these study skills, it is

helpful to expose them to a variety of ways to practise words and their definitions and let them choose the manner which is comfortable for them.

10. 2 Semantic elaboration

Both Hague (1987) and Machalias (1991) conclude that meaningful exercises or classroom activities which promote formation of associations and therefore build up students' semantic networks are effective for long-term retention. These kinds of

activities have been mentioned earlier because of their importance in integrating new words with old, promoting deep levels of encoding, and establishing concreteness. In addition, there is evidence that combining semantic elaboration with the keyword approach builds memory

traces, i.e. mental records of the experience, and retrieval paths which are stronger than those created by the mnemonic device alone.

10.2.1 Personal category sheets

Learners can store new vocabulary as it arises on appropriate category sheets which they can keep in a ring binder or on separate pages of a notebook. The sheets could have headings such as topic areas or

situations, these headings being selected by the student himself. As he acquires new vocabulary, he can add to the sheets and cross-reference them where necessary. He will have to decide where to categorise and when to open a new category sheet. The information given on these

sheets (i.e. meaning, perhaps translation, part of speech and an example) should be comprehensive as suggested above.

It is also possible for learners to use index cards; each card would contain information about lexical items and their derivatives, and the cards could be filed thematically. This is perhaps a rather cumbersome practice in the classroom, but

may well suit individual learners for home use.

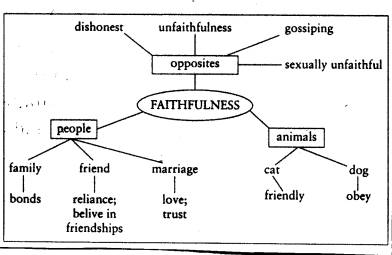

10.2.2 Semantic mapping

10.2.2.1 ASSOCIATIONS

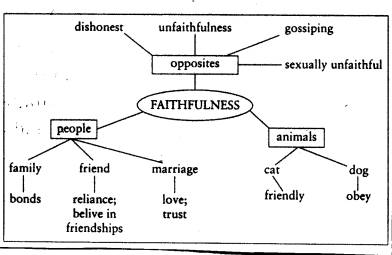

Semantic mapping generally refers to brainstorming associations which a word has and then diagramming the results. For example, when asked to give words they thought of when they

heard the word “faithfulness”, low-intermediate ESL students generated sixteen words or phrases: cat, friend, family, reliance, trust, dishonest, unfaithfulness, believe in friendships, bonds, obey, dog, friendly, sexual unfaithful, gossiping, marriage, love. After clustering

words which they felt went together, they mapped the relationships between these words as follows:

|

Because it is possible to analyze words in different ways and because features may be difficult to agree upon, semantic feature analysis and semantic mapping promote a great deal

of group interaction. Over time, the learners may add new words to then charts and maps. These semantic exercises will then no only be visual reminders of links in the lexicon but of the learner’s expanding vocabulary.

But be careful: Overusing these semantic exercises to introduce new words or less frequent vocabulary with L2 learners may result in overload.

|

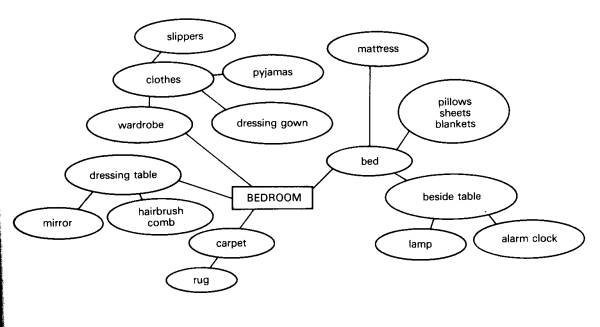

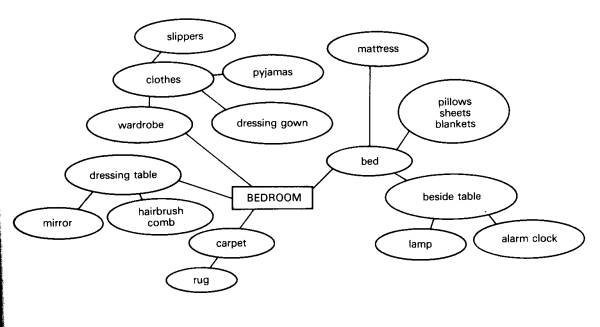

10.2.2.2 WORD FIELD DIAGRAMS

Visuals are an extremely useful framework for storage of lexis, and they can be used to highlight the relationships between items. Word field diagrams are of interest here and the example below (from Use Your

Dictionary, Underhill, 1980) could be used as a testing activity by omitting some of the items. Learners could also be asked to organise their own diagrams of this type.

1

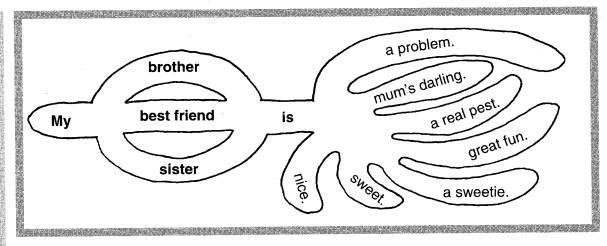

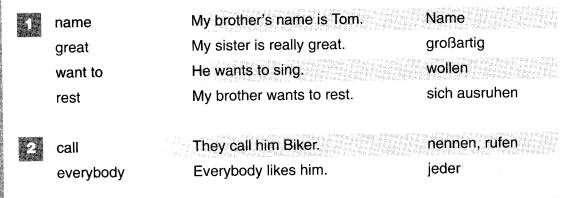

0.2.3 Wordfields

At the end of each Unit of THE NEW YOU&ME you can find Wordfields in the Workbook. Wordfields are arranged according to associative items. Here also structures are included – when they can be

linked with the same semantic field. Students are asked to remember the Wordfields the same way as they are lay-outed in the book.

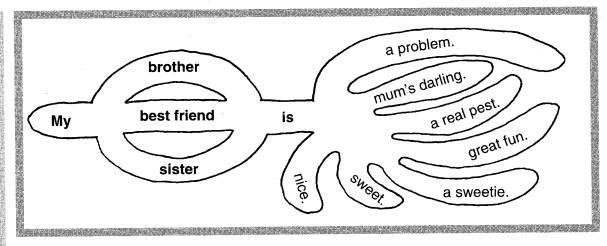

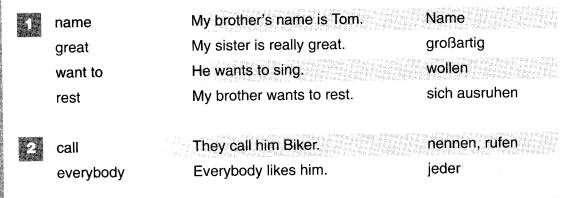

Example:

10.2.4

Categorising

Students can also be asked to categorise items; for example, putting the hyponyms in a list under the appropriate super ordinate term:

|

strawberry

|

carrot

|

FRUIT

|

VEGETABLES

|

|

onion

|

cauliflower

|

|

|

|

potato

|

peach

|

|

|

|

cherry

|

pea

|

|

|

|

pineapple

|

celery

|

|

|

|

pear

|

|

|

|

Dictionaries often give useful visuals enable students to do this type of exercise.

10.2.5 Word – semantic fields

The grid which follows could be done on the blackboard by the students themselves, after which it can be done as a group or homework activity by giving the students only one column of information (perhaps the

first) and asking them to supply the rest.

| PROFESSION

|

PLACE OF WORK

|

DUTIES

|

| surgeon

|

hospital / clinic

|

to operate on people

, to treat medical problems

|

| mechanic

|

garage

|

to repair cars, lorries, etc.

, to put in and repair:

|

| plumber

|

buildings / houses

|

water pipes e.g. in the bathrooms, kitchens, central heating

|

| Foreman

|

Factory / worksite

|

To supervise other workers

|

| Photographer

|

Studio or anywhere

|

To take photos, commercially or artistically and to develop and print them |

| Lawyer

|

Office / law courts

|

To advise people about the law

, to represent them in court

|

10.2.6 Random items

A useful vocabulary revision activity is to write on the blackboard a number of vocabulary items which your students have learnt during the last few lessons. Jumble the words so that they do not appear on the blackboard in listed categories.

Ask students to work alone to categorise the items into three or four groups. It is best if this type of organization is subjective at least in the initial stages; it is important to allow the learners to make their own decisions about how they wish to arrange the items. Their groupings may be grammatical or semantic; they may wish to group items by colour,

shape, function, pleasantness or unpleasantness, activity, etc. Once the students have organised the vocabulary in their own way, ask them to explain their grouping to the class or to discuss this in small groups. This can be a useful way of checking that the students have

understood the items as well as providing an opportunity for them to store and organise subjectively.

10.2.7 Words in context

You can find that type of presentation in the Workbook of The NEW YOU&ME at the end of each Unit. There you can find the English word – a sentence using this word in

context – the German translation.

Example:

Ask the students to copy the “English word” and the “word in context sentence” into a note book. If the student knows the meaning it is not important to write the

German translation as well. The student is supposed to remember the word in the context, not the translation.

Note: Make sure that you check vocabulary the same way as you ask the students to remember them.

10.2.8

Semantic feature analysis

In semantic feature analysis students are asked to complete a diagram with pluses and minuses (or yes's and no's) as a way to distinguish between meaning features.

| |

affect with wonder

|

because

unexpected

|

because difficult to

believe |

so s to cause confusion

|

so as to leave one helpless to act or think

|

| surprise

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| astonish

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

| amaze

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

| astound

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

| flabbergast

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

10.2.9 Ordering

Ordering or classifying words is anther technique which helps students distinguish differences in meaning and organize words to enhance retention. When students are asked to

arrange a list of words in a specific order, organizing the words will integrate new information with the old and, therefore, establish memory links.

Having students generate the scrambled lists which include the target vocabulary is another opportunity to increase depth of processing.

Examples:

| - whole : parts

|

| (scrambled): silk paper

artificial flowers plastic

|

| (ordered): artificial flowers: silk,

paper, plastic

|

|

|

| -

degree (of responsibility)

|

| (scrambled): accountant

auditor bookkeeper

|

| (ordered): bookkeeper accountant auditor

|

| degree of (disagreement)

|

| (scrambled): discuss

fight quarrel

|

| (ordered): discuss quarrel fight

|

10.2.10 Pictorial schemata

Creating grids or diagrams is another semantic strategy. Whether they are teacher- or student-generated grids, these visual devices help students distinguish the differences

between similar words and set up memory traces of the specific occurrence. Scales or clines, Venn diagram, and tree diagrams are especially interesting for group work when teachers present words for these pictorial schemata in scrambled order. Students are then asked to

unscramble the words by putting them in a logical order.

Scale or cline:

Arrange in order from happy to sad: upset, pleased, overjoyed, broken-hearted, indifferent

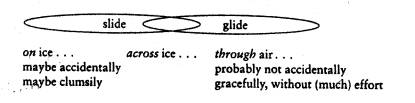

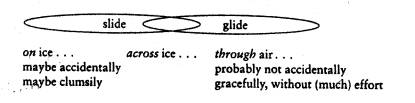

Venn diagram:

Illustrate how “slide” or “glide” are different.

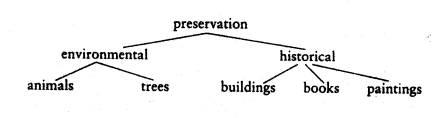

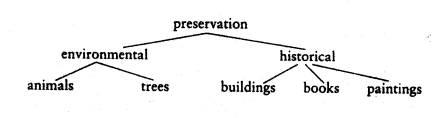

Tree diagram:

Classify the parts of preservation.

These semantic techniques ask students to deeply process words by organizing them and making their meanings visual and more concrete.

10.3

Mnemonic devices

Mnemonic devices are aids to memory. They may be verbal, visual or a combination of both. Advocates of mnemonic devices believe that they are so efficient in storing words that the mind is then freer to deal with

comprehension. The most common verbal mnemonic device is using the rhyming of poetry or song to enhance memory. According to Baddeley (1990), this combining of rhyme with meaning has a very powerful effect on retention. That many of us can still remember lines from songs

taught in our first year in a foreign language class attests to the powerfulness of this memory aid.

Regarding visual devices, in early stages, students can benefit from word/picture

activities which set up mental links. Because of personal investment, student-generated visuals are even more memorable. A classroom version of the party game

Pictionary is usually a lively, productive way to associate a picture with a word. Days later, holding up their hurried drawings, students will remember the target words they laboured to visualize for their team.

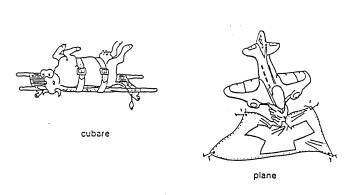

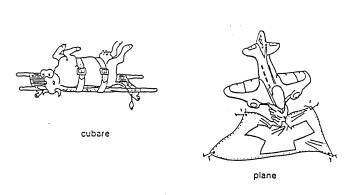

Of all the mnemonic devices, the most often studied with the most impressive results is a technique which employs both art acoustic and a visual image: Atkinson's (1975) keyword method. The keyword method has two steps: the student chooses a word

in L1 which is acoustically similar to the one to be learned and then creates a visual image of that L1 word along with the L2 meaning. For example, to teach the Turkish word for door “kapi”, an English speaker could choose the slang word for policeman, 'cop', as

being acoustically similar and then imagines a policeman pounding on a door. Every time the student encounters the word “kapi”, the image of the policeman will be reinvoked, thus leading to the meaning of 'door'. Although effective with all age groups, children find

this technique to be an especially enjoyable way to learn vocabulary. Student-generated images have been found to be effective, but images can also be provided by the instructor. It can be assumed that while creating these images, stronger links are set up since they require the

student to do deeper mental processing as they integrate the new word with a familiar one.

Students can benefit in two ways from experiences with mnemonic devices. Not only do they acquire the target language, but they also are taught aids to memory which can be applied top other areas of knowledge acquisition.

10.4 Word unit analysis

The number of words to be acquired in a new language can be overwhelming! The estimates of the number of words in English range from half a million to over two million,

but native speakers have a much smaller number of words in their receptive or productive vocabularies, depending

on their age and educational background. For example, an undergraduate might only have a vocabulary of 20,000 words.

Ask students to analyze words. For example, the word innate routinely comes up and students rarely know the meaning of the word or its root, lnat'. However, once we review what the prefix 'in' means, and I elicit other

words containing the root 'nat” (native, natural, nation, nationality, prenatal), someone in the class can infer the meaning, birth, from their understanding of the brainstormed words. In this way, word unit analysis asks learners to compare the new word with known words in order to get to their core meaning,. Because it demands a deeper level of processing and reactivation of old,

known words with the new, it has the potential of enhancing long-term storage.

10.5

Collocations and lexis phrases

Since collocational relationships, words which commonly go together, appear to have very powerful and long-lasting links in the lexicon, providing opportunities to practice

collocations is a worthwhile activity.

Oral activities using to-be-learned words have the advantage of breaking up the class routine, getting students out of their seats, and experiencing words in a variety of ways with aural and oral reinforcement.

a) Memorizing and acting out dialogues

Dialogues have the advantage of putting words directly into productive vocabulary.

b) Role playing

It is an option for more spontaneous oral practice of vocabulary.

c) Oral interview

Variations on the oral interview provide a range of communicative practice with target vocabulary. Students can share one-on-one how a word relates to personal experience, rotate to new partners, or snowball to

increasingly larger groups. Information gathering activities also highlight target vocabulary.

TOP